First lesson: Improved Understanding in Attack

In an intriguing tale from Ancient Chinese philosophy, Butcher Ding was summoned by his village leader to perform a task that overwhelmed his fellow butchers who seemed to possess the same level of blade wielding skills; he had to sacrifice an ox as part of a ritual to consecrate a sacred bell. Unfazed by the task at hand, Ding went about cutting up the ox with nonchalant ease. When an astonished village chief demanded an explanation, Ding reveals, “The secret is to not approach the problem with your eyes, but with your spirit.” Novices like us probably won’t be able to entirely comprehend Butcher Ding’s methods but it is said that Jack Wilshere and Olivier Giroud offered similar explanations when asked about their wonder goal against Norwich City. (Though Wilshere supplied the final touch, can it really be counted as his goal solely?).

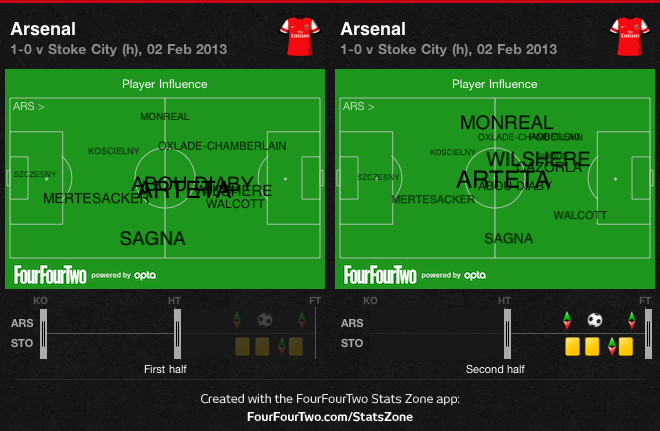

There are two fundamental requirements to breakdown parked buses; either depend on players to get past opponents through pace and dribbling ability or depend on fast circulation and understanding between players. Arsene Wenger is the type of manager who relies on his players’ combination play to break down defences and it’s quite fair to conclude the spontaneous understanding between the players reached its peak this season. The first half of the season saw some breathtaking moves from Arsenal with Aaron Ramsey, Mesut Ozil, Jack Wilshere and Olivier Giroud combining like brothers having a kick around in the backyard. The French striker did an admirable job with his back to the goal, letting the midfielders create play by knocking passes off him.

For the second part of the season, Arsenal had been missing those runs from deep (from Ramsey) that glue Arsenal’s passing game together. Because without somebody breaking into space, who have Arsenal’s myriad of ball players got to pass it to? Instead, play in that period would look soporific, lacking urgency and easy to pick off. Indeed, the way Arsenal play, bumping passes off each other, it requires little triggers so that the players know when to move their passing game up a gear. Ozil is brilliant at that, moving quietly into space, trading a few innocuous passes, always with his head up waiting for the moment to increase the tempo and his team-mates seem to feed off that. Ditto Ramsey’s runs from deep.

To play truly great attacking football, a blind instinctive awareness – or “blind understanding” as Wenger calls it – of one’s teammates is fundamental and at moments this season Arsenal played attacking football of the highest quality.

Second Lesson: Is Mertesacker-Koscielny the best?

Per Mertesacker and Laurent Koscielny complement each other perfectly; Koscielny is the fast and aggressive man marker while Mertesacker is the solid presence who sweeps behind; Koscielny is the forward thinking instigator while Mertesacker is one of the safest distributors around, etc. The partnership has had an appreciable season and has contributed immensely to achieving the second highest number of clean sheets in the Premier League, and conceding the fourth least number of goals. On average, the partnership averages 4.5 interceptions and 1.8 offside calls per game while only being dribbled past 0.7 times per game. Laurent Koscielny’s and Per Mertesacker’s value in the attacking phase is unmatched as they top the passing accuracy charts with the former passing with 93.5% success and Mertesacker with 93%(he attempted 538 more passes) success. These rudimentary statistics don’t tell the complete story but keen observers will agree that the ‘Mertescielny’ is one of the best partnerships in the world.

Indeed, their partnership follows what has become a trend whenever teams play a back four: one of the centre-backs attack and the other covers. Against two strikers, though, the duo has shown how much their relationship has prospered because against such a set-up, both defenders have to mark (as opposed to playing against a lone-striker where Mertesacker will normally attack the ball and Koscielny drops back). As such, that puts demands on the holding midfielder to provide cover, which leads us on to the next lesson…

Third Lesson: Defensive Reinforcements

At the beginning of the season, the signing of Mathieu Flamini seemed an astute one from Le Boss as he performed dependably in his first few games. But as the season progressed, his weaknesses became apparent and playing him alongside Mikel Arteta only magnified them. In attack, Flamini offers almost nothing other than safe passing (91% success) and decent running, which means going backwards, he tried to compensate with his defensive positioning, which more than once, most notably against Southampton, Swansea has cost the team (click for image example). Mikel Arteta did slightly better than Flamini but his susceptibility to pace has become a prominent weakness of his. He has also been quite easy to dribble past, being bypassed 1.7 times per game. This figure is very much on the higher side as Flamini is dribbled passed less, at 0.4 times per game, with one particular weakness of Arteta is that he allows opponent midfielders to blitz past him in counters far too easily. That figure, though, chimes with what his game is about: Arteta loves to press up the pitch, looking to win the ball back quickly, an underrated trait of his. Flamini on the other hand brings hustle but his tendency is to drop deeper and cover spaces.

Another defensive midfielder would be imperative, particularly with Bacary Sagna leaving – one who slots in between the centre-backs in the build up to help better utilize the full backs as they can be important weapons to breakdown packed defences. Arteta’s distribution skills are better than he is given credit for (although his passing can be slightly on the slower side at times) but a defensive midfielder with better defensive positioning would help improve Arsenal’s defensive stability.

Fourth Lesson: Aaron Ramsey is the man

This is the most obvious lesson of the seven. Aaron Ramsey had a blistering first half of the season when he was our best player by miles. Then he got injured for a while before coming back to deliver top four in the premier league and an FA Cup. Last season he was praised for his reliable performances alongside Arteta, where he combined intelligent running and an unrivalled work rate to become an important member of the team. This season saw him transform into an insanely confident footballer with outrageous skills as he went on an almost unstoppable run where he kept scoring, assisting and embarrassing opponents much to the joy of the Gunners faithful. Arsene Wenger kept reiterating Aaron Ramsey’s hunger to improve (he seems to have that Thierry Henry-like obsession about football) and this has seen him become the best player in our team. In the FA Cup final against Hull City, one could see Aaron Ramsey trying hard to force the winner in extra time. Despite a few improbable attempts from long range, he kept trying and eventually scored and it is this quality of delivering in decisive moments that has proved vital for Arsenal many a times. It is almost like there is a ‘What? What else were you expecting?’ kind of brash arrogance (in a subtle way, if that is possible) about him and it would be great if it rubs off on the team.

Fifth Lesson: Mesut Ozil provided only a glimpse

Big things were expected from Mesut Ozil and he seemed to be on the right track as he scored thrice and assisted four times in his first seven games. Since then he has only three goals and seven assists and most have been swift to brand him a flop. To do so would be very harsh on the German playmaker as his real contribution to Arsenal’s possession play shouldn’t be judged just by his assists and goals scored statistics.

He was expected to play the ‘Bergkamp role’, playing behind Olivier Giroud to be at the end of moves. But Ozil’s duties lie slightly deeper as he is given the responsibility to dictate play and perform an important role in the build up. As Wenger says, “the quality of his passing slowly drains the opponent as he passes always the ball when you do not want him to do it. That slowly allows us to take over.” Thus, extra layers are added to Ozil’s worth to the side; he’s all at once, an attacking weapon, a master controller and a defensive force, allowing Arsenal to keep opponents at arm’s length, and luring them into a sense of comfort that is also complacent.

Ozil averages 63 passes per game (behind only Mikel Arteta and Aaron Ramsey in the team), constantly peeling to either wings (his preferred control centre seems to be that channel off the centre towards the right wing) to try various angles and combinations. His combination with Aaron Ramsey has been one of the more fruitful ones and has played a substantial part in the latter’s rise. Arsene Wenger is confident that the German wizard would deserve a statue at the Emirates by the time he leaves Arsenal but Mesut Ozil will have to elevate his game by a notch to attain such levels. Everyone knows he can.

Sixth Lesson: Olivier Giroud requires competition

Whoscored.com rates Olivier Giroud as Arsenal’s second best player behind Aaron Ramsey. While that is a little farfetched, it shows Giroud has had an acceptable season as Arsenal’s Number One Striker™. Netting 18 times and providing 9 assists in 43 games is decent output for a forward but Giroud has that wildly irritating knack of going into a run where it looks exceedingly improbable for him to score.

His major assets are his link up play and aerial ability, although his combination can desert him at times due to a first touch which at its best, can be silky smooth like delicate fingers working up Chantilly lace or just plain awful. Arsene Wenger took a huge gamble by not bringing in strikers in the transfer window and he was forced to rely entirely on the Frenchman who was bound to be affected by fatigue. As the season wore on, it wasn’t necessarily his finishing skills that let Arsenal down but his propensity, as the lone striker, to play a little bit like a totem pole. That works when there are runners getting beyond him – Ramsey and Walcott are key – but often, it relies on moves being perfect and that’s not always possible. When Yaya Sanogo has deputised, though he has still yet to break his mark for the club, it shows what value a striker can add purely by running the channels – that means sometimes away from play – stretching defences and creating space for runners. Indeed, in the cup final, Giroud was probably the one who profited most from Sanogo’s presence, as this meant he was afforded the freedom to do what he’s unable to do when he plays up front on his own: run. It seems unlikely, unless he adds a mean streak to his game, that Sanogo will push Giroud hard for a starting spot in the near future, nor is a switch to a 4-4-2 system in the offing, meaning it is absolutely necessary to bring in a different type of striker to compete with Giroud.

Seventh Lesson: This team can play both ways

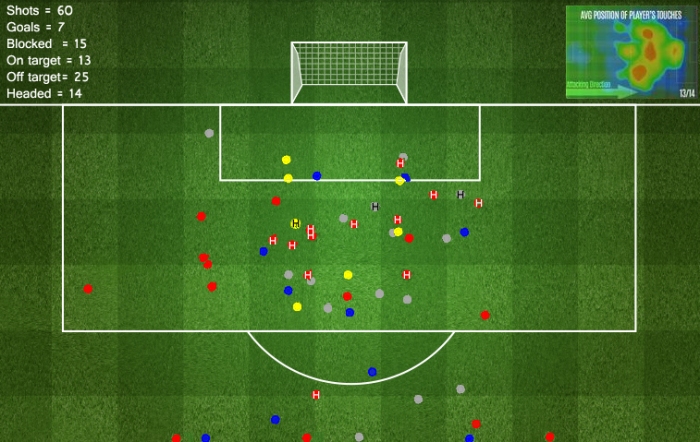

It comes as a surprise that Arsenal hasn’t topped the possession table (they’re fourth behind Southampton, ManchesterCity and Swansea) this season given that they’ve done so in each of the last three seasons. This season, Arsenal has conceded that extra bit of possession to maximize efficiency in ‘moments’. Fewer shots have been taken this season (13.8 compared to 15.7) and creating qualitatively better chances seems to have been the focus.

The trend in the Premier League this year has been not to press defences (Southampton being the exception; they’ve kept 58% possession on average mainly due to their ball winning mechanisms) but to forming two compact banks of four. Arsenal did the same last season and showed their prowess on the counter many a times, which makes it even more disappointing that Arsenal lost to Liverpool and Chelsea in that manner due to flawed strategy. It is apparent that this team has the personnel to execute both strategies effectively and Arsene Wenger has done reasonably well to juggle his approach midway games.

Follow Karthik on Twitter – @thinktankkv